A Different Way to Think About Recursion

In order to understand recursion you must first understand recursion

If you are in a hurry, you can skip directly to the summary section.

Recursion is a simple but very confusing concept. When I first learned about it, I was confused as to how a function can call itself. I was working on some code the other day, and I had to use recursion to solve a problem, and while I was writing the function, I had a realization that changed how I look at recursion. I would like to share that with you here today.

First, let’s start with a brief explanation of what recursion is, in case it is new to you. If you already know what it is, you can skip to the next section.

What is recursion?

Recursion is a programming concept that arises from the Functional Programming paradigm. The world of functional programming is built on a few key principles:

- minimal to no mutation of external states. Everything that a function does must be contained within itself, with no side effects. This means a function should only rely on its inputs to generate its outputs and not manipulate any external variables or entities, including their inputs, unless absolutely necessary.

- Functions must be deterministic. Given the same inputs, the same outputs should be expected. This is because there are no side effects, as mentioned above.

- All functions must return something. Functions have inputs and produce outputs, and since there should not be any side effects, the best way to know the output of a function is to read the function’s return values. A function that adheres to the first two principals is known as a pure function. Pure functions are stateless in design because they do not rely on or manipulate external states.

Ok, so with those core pillars of functional programming in mind, we can tackle recursion. To answer the main question, here is my simple definition of recursion:

Recursion is when a function calls itself with different inputs until a base case is reached.

It’s not a perfect definition, but it captures everything that is needed for our purposes today. A recursive function, if written correctly, is an example of a pure function. It takes some input, iterates over it, produces some output, and does not mutate any external states. Recursive functions must also have a return value, or they will continue forever. In the case of Python, you would reach the maximum allowed recursion depth.

Factorial Example

A simple example of a recursive function is a factorial calculator function:

def factorial(n:int) -> int:

if n == 1:

return 1

return n * factorial(n-1)

A factorial is a product of all integers from 1 up to a limit $n$, like this: $$n \times (n-1) \times (n-2) \times ..\times (n-(n-1))$$

The function does exactly this. It takes an integer $n$ and multiplies it by the value returned by calling the function again with the value below $n$. The base case in this case is when we reach $1$ which is $n-(n-1)$. At this point, we know we have gone through all the values from where we started.

The Rethinking

When I learned about recursion, I was both confused and mesmerized by what I was looking at. Imagine being given a task, and instead of doing all of it by yourself, you spawn a clone of yourself to handle a part of it, and the clone does the same, each new clone handling smaller and smaller parts of the task. I wanted to use it everywhere but found it very tricky to implement. Clones are very slippery things to mess with.

It was not until today, when I was tackling a classic recursion problem of tree traversal, that I reflected on what was actually going on. I had always had a hard time figuring out what the base case was and how to represent it in the function, together with the information I would need to pass to the function on the recursive call.

I thought about what was happening and came to this conclusion:

Recursion is about simplifying inputs going forward and clarifying going backwards.

If a light bulb doesn’t immediately go explode in your head, I hope it will by the end of the article. Let’s look at that factorial description again: $$n \times (n-1) \times (n-2) \times ..\times (n-(n-1))$$

Whether you use $PEMDAS$ or $BODMAS$, the same thing always comes first in the order of operations: parenthesis. Therefore, if we were to evaluate the expression for a factorial, we would have to start from the right towards the left. Basically, start at the end and work our way back to the beginning.

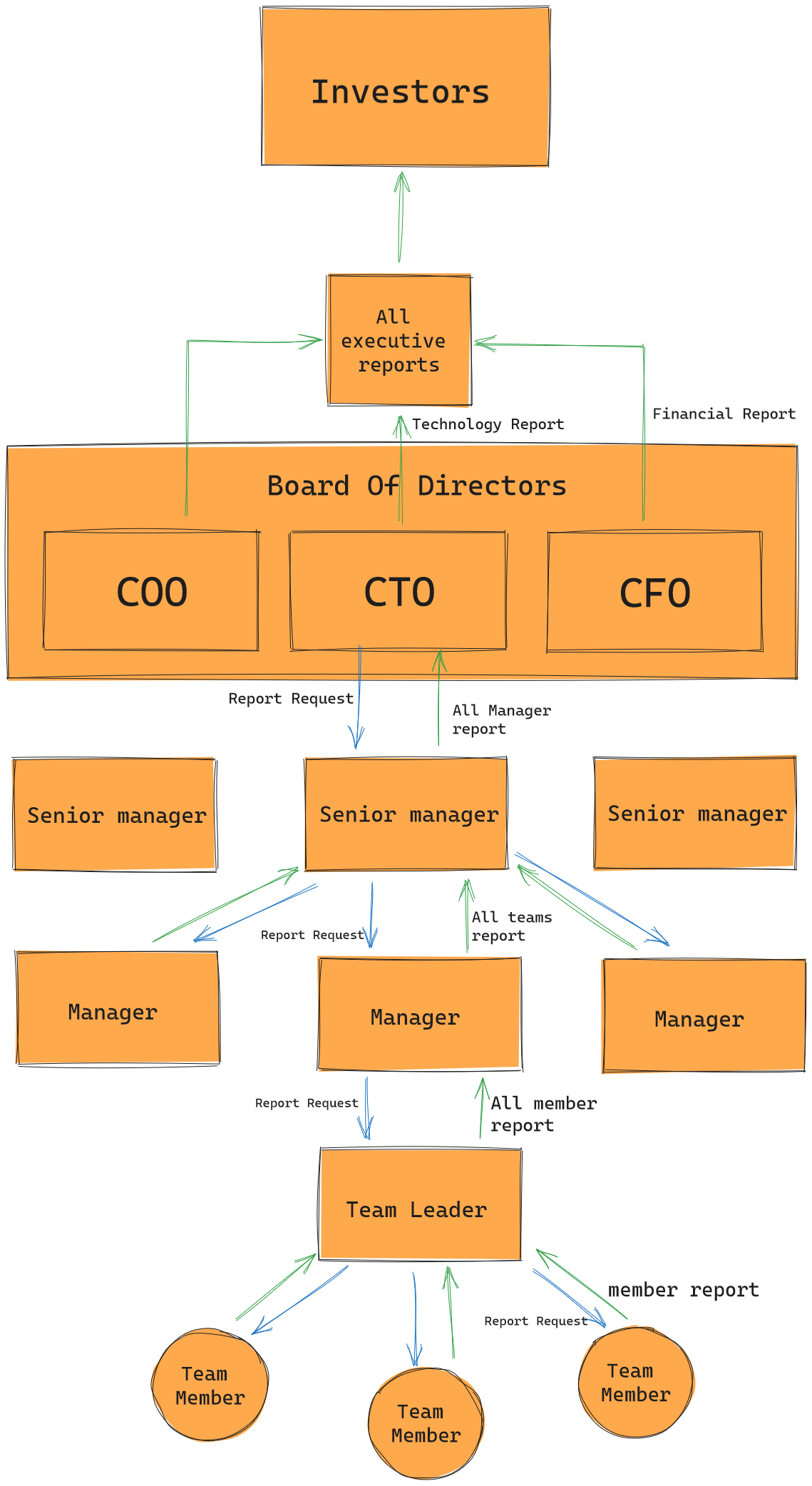

Corporate Structure Example

Imagine that the investors of a large tech company want a status report for the whole company. The board calls a meeting of the different leaders of the company, like the CFO and CTO, and each member is tasked with generating reports for their part of the company. The CTO calls the departmental managers below him and asks for a similar report, but only for the technology side, and the senior managers go to the junior manager, and they go to the team leaders below them and ask for the same thing. Lastly, each team member reports to their team leader about what they are working on and the status of the projects.

The team members are at the bottom of the chain and have the actual information. They don’t need to ask anyone else below them and are the “base case”. So now each team member gives a report, which the team leader compiles together with a report of their own activities and sends it up to the managers. The managers compile all reports from the teams they manage and add information about their office before pushing it up. This goes on until we finally get back to the board, which then compiles all this information and gives it to the investors. The investors can then decide how many private jets they should get for their spouses.

At each level going down, the information requested gets simpler and simpler relative to the complexity of a large company. The person requesting the information at each stage has some level of uncertainty because they may not know the details of what is happening within each node below them. On the way up, the person at each node is able to piece together the information returned from each node to form a clear picture of what is going on and pass it on to the person above.

Code Example

When we no longer have any more uncertainty about what information the function should return, we have reached the bottom of the tree, the core of the nesting, the base case. From here, it is about compiling the information going up. Each stage provides more and more certainty to the caller. Now the tricky part is deciding how to ‘compile’ this information and what information is uncertain and needs to be clarified by a ’lesser’ function call. So going down the recursion stack trace, we are simplifying the input, and going up, we are providing clarification and reducing uncertainty. To go back to the factorial, we see that at each stage, we are unsure of what the total product of the numbers that come before is. So we simplify the input by taking away the current value of $N$ in each recursive call until we have certainty that the product of 1 and itself is 1.

Let’s take a look at a small example similar to the problem I was tackling when I came to this realization. We have a directory structure that looks like this:

{

"Documents": {

"Proposal.docx": None,

"Report": {"AnnualReport.pdf": None, "Financials.xlsx": None},

},

"Downloads": {"picture1.jpg": None, "picture2.jpg": None},

}

We need to generate an array of all file path strings after walking them. You know you have reached the end of a file path when you encounter a key that has a value of None. A key is considered a directory if it has a dict as a value.

Here is an example of how to solve the problem in Python.

def list_files(current_node, current_path=""):

file_list = []

for k, v in current_node.items():

if v != None:

file_list.extend(list_files(v, f"{current_path}/{k}"))

else:

file_list.append(f"{current_path}/{k}")

return file_list

For each node (directory) we encounter, we do not know which files, if any, are contained in each of the nodes within. This is uncertainty. We know all the files that are in the current node but not below, so we call the function again for sub-node sub-node within the current node. We simplify the input and call the function again.

Eventually, we get to a place with no uncertainty and also to the point at which we cannot make the input any smaller or simpler without breaking things. At this point, we have reached the base case. From here, we begin returning values, and each value we return builds on other values that were returned from other nodes or the calling node. All the way up to the genesis node.

Summary

If you are no longer in such a hurry, jump back to the top

The key takeaway from this article is recursion is about simplifying inputs going forward and clarifying going backwards. Which briefly means:

- If you want to write a good recursive function, you should aim to make it a pure and deterministic function. It should only take the inputs it requires and not make any mutations to external states.

- If you are struggling to come up with the structure, think of the final recursive call and imagine the simplest form of the input that has absolute certainty. Make that your base case. In the case of the factorial, it was

n==1was the simplest form ofnwhose factors we know about. In the case of the directory traversal, it wasv==None. - Build upon that base case to determine how you can simplify the inputs for each round.

- Make it such that the return value for each round of recursion is a absolute version of what was given to as input.

Conclusion

I hope this article helped change how you look at recursion for the better and that you will now be able to write recursive factions with confidence and make fewer mistakes.

Thank you for reading. You can reach out for comments, corrections and compliments via email, or on twitter.